Thank Lee Wardlaw for coming by Kid Lit Frenzy and answering a few questions from a fellow cat lover. I love Won Ton and his new buddy Chopstick.

You have an apparent love of poetry. What poetry/what poet has been most influential on you as an official or unofficial mentor?

If I’m forced to choose just one (to me, poets are like potato chips—how can you possibly stop at one?!), it must be Valerie Worth.

Worth’s book All the Small Poems and Fourteen More (FSG, 1994) is brilliant. Each poem is a compact observation of something ordinary, something you might never in a million years think of writing a poem about—a safety pin, asparagus, a pile of rags!—yet in a few spare but perfect words she turns that mundane object into something fresh and wow-worthy. Part of Worth’s talent lies in her ability to observe, to use all her senses to appreciate the complex and unique beauty in life’s simple things.

Won Ton & Won Ton and Chopstick are written in Haiku. I imagine that you have played with a variety of poetry styles. Any favorites and what ones have challenged you the most?

Haiku is obviously a favorite! In third grade, as a prize for perfect school attendance, I received a book of haiku poetry written by Matsuo Bashō (1644-1694). Centuries after his death, Bashō is still considered the world’s greatest haiku master. (I pay homage to him at the end of Won Ton and Chopstick.) As a child, I loved my Bashō book (yes, I still have it!), and I’ve been writing haiku ever since. In fact, eons ago, when doing my first student teaching assignment in a K-3rd grade classroom, the first lesson I taught was on haiku!

Haiku appeals to me because of its immediacy, its focus on one moment in time: Now. Its rules appeal to me, too. I have ADHD, so without structure and specific “rules,” I tend to get overwhelmed. There’s something safe and soothing to me about writing poetry that has specific boundaries. Some people find haiku too constricting, but within its parameters, I am free to do whatever I like.

As to the style of poetry that has challenged me the most? Sonnets. I suck at sonnets. Is that too crude to say? How about: Me + Writing Sonnets = Headache.

Poetry seems to be a form of writing that is less intimidating for English Language Learners and others. What are some of your tips for teachers to share poetry writing with children?

First: I highly recommend teachers start with Poem-Making: Ways to Begin Writing Poetry by Myra Cohn Livingston (HarperCollins, 1991). It’s an easy-to-read, easy-to-understand primer that covers voice, sound, rhyme, rhythm, repetition, and various forms of poetry. The book is actually geared for ages 9-13, but everyone can learn from it. I did!

Second: If you’re going to share poetry writing with children, you must share poetry! You must read poetry aloud. Every. Single. Day. It only takes a few minutes. If teachers aren’t sure how or where to start, I recommend The Poetry Friday Anthology: Poems for the School Year with Connections to the Common Core compiled by Sylvia Vardell and Janet Wong. (Pomelo Books 2012)

Vardell and Wong have produced several other useful, creative, and fun anthologies, such as The Poetry Friday Anthology for Science and The Poetry Friday Anthology for Celebrations (the latter features Spanish translations of each poem).

Third: An important key to writing good poetry is Observation. (Remember my answer to Question #1?) So take students outside! Before children can become poets, they must first act like scientists. They must use all their senses to explore and absorb the world around them. Poet Kristine O’Connell George has some excellent observation tips and activities on her website.

Can you describe your collaborative process with Eugene Yelchin (if any) and did it change this time around?

It’s a misconception that authors and illustrators collaborate when creating picture books. Here’s how it works: I submit a manuscript; my editor then hires an illustrator whose style, medium, technique, etc., she thinks will best bring my words to life. With Won Ton, I had no contact with Eugene (other than an email introducing myself) prior to the book’s publication. I had no say in what Won Ton would look like, or how the various scenes would be illustrated. This is as it should be. I certainly wouldn’t have wanted Eugene looking over my shoulder as I wrote, saying: “Hey, I’m not great at drawing cats. Couldn’t Won Ton be a schnauzer? I’m super at schnauzers!”

All that being said, I did get to see Eugene’s initial sketches for both books. For Won Ton and Chopstick, I made two minor suggestions.

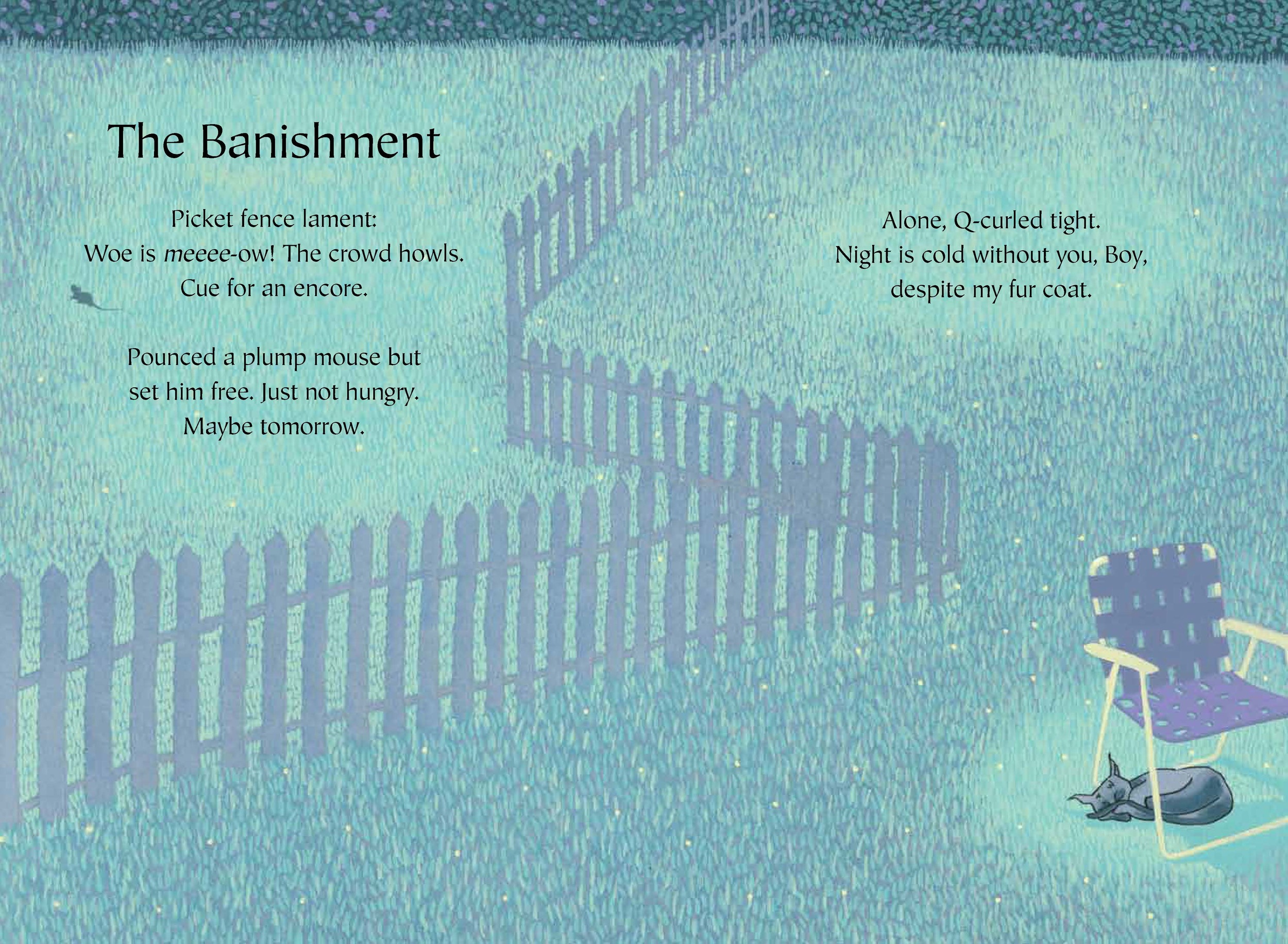

First, in the two-page spread called The Banishment, there is a poem that reads: